Presence

The act of

transitioning from seed to plant, from expressions of sprouting to growing,

embodies a conversation about presence. The drama of a sprout shooting clearly

changes its situation in the world; it explodes and cuts open time-space

constellations and introduces archives of doing presences, choreographies of

presence-ing. Thinking a vegetal intervention towards a conception of presence

asks about presence-ing in correspondence with modes of absence, including life

and nonlife. “The world dies from each absence; the world bursts from absence.

[ . . . ] Every sensation of every being of the world is a mode

through which the world lives and feels itself, and through which it exists.

And every sensation of every being of the world causes all the beings of the

world to feel and think themselves differently”: thus philosopher of science

Vinciane Despret moves together with two passenger pigeons, Martha and George,

who died at the Cincinnati Zoo at the beginning of the twentieth century as the

last of their species.[1]She writes a little miniature for performance artist Antonia Baehr and Friends,

from which this is a brief quote, contributing to a series of their extinct

dances. Despret’s lyrical retrospective for and of a species’ (dis)appearance

on this planet describes the pigeons’ wings’ play in dialogue with the sun,

attuned to the winds, “the joy of being innumerable and of forming one

perfectly attuned being,”[2]as well as the taste of pigeon pie. She unfolds a complex understanding of what

it means to be in/of the world: a self-thinking, self-writing differential that

everything is part of. Complicating the notion of presence reaching into the

past while co-constituting the now, she writes about a phenomenon she could not

herself have been present to witness—or could she? Is it so that a layer of

presence is archaeological, a spatiotemporal imprint from all that is not of

the moment but present in it? Importantly, Despret disposes any layer of

sentimentality and mourning in her approach to think extinction in this regard,

and instead she turns to joy. The German translation of “presence”—Anwesenheit and Gegenwart—exemplifies the term’s layered construction. Taking a closer look at the German terminology uncovers two different perspectives of presence: Anwesenheit embraces -wesen-, which in antiquated linguistic usage can be a verb as well, meaning “to be present”; today, the expression refers mainly to an entity. That being, able to be receptive to its surroundings, is present through its capacity of performing perceptive entity-ness. The other, Gegenwart, obscures “the being” (wesen) within an opposition Gegen- of the present against a past or future, while the ending -wart, which indicates “waiting for,” suspends or maybe even bursts open what appears as a present unit. The resolution of the present dilutes in the arc from past to future, and in doing so, dissents from any idea of linearity. The distinction between the two actually provides a shared ground, conceiving the term’s durational and processual dimensions together. Thinking modes of presence-ing requires a relation prior to the perceiver and the perceived. This relation or set of relations is what makes instances of presence-ing appear, take shape, and leave their signatures on the planet, above- and belowground. Different states of attention and sensory awareness might allow us to trace other forms of presences in unusual graininess or resolution.

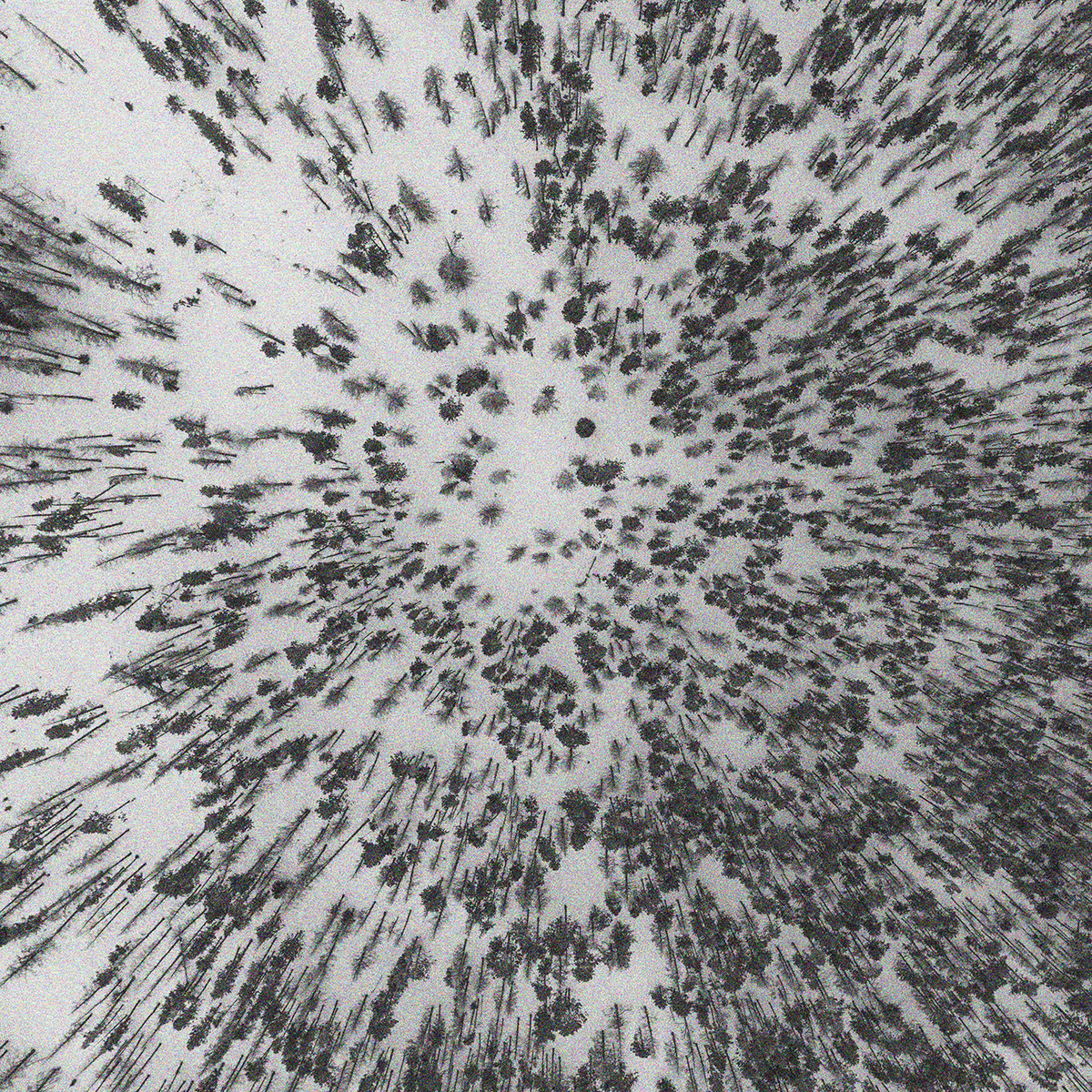

The initial dance of the pigeon couple expresses a mode of presence that lets different timescapes collide in the moment. Or, put differently, presence is enmeshed with the entirety of the planet’s past actualizing itself. One can only think presence through all their absences, and this implies a relationship to the potential of co-presences, in all that might or could happen. The collective and time-expanding nature of the term is only more apparent when considering plant life. The seed’s capacity to exist as inert matter for centuries until latent awakening or reanimation dramatically extends the concept of presence:[3]its temporal dimension, but also its mediated physicality. In particular, the notion of a transitory state between wakefulness and dormancy, as a collective agency in the relationality of one seed’s “successful” reanimation and all seeds’ potential germination activities. The conditions of reawakenings can be very orchestrated, as this historic anecdote exemplifies: “The ‘sacred lotus’ (Nelumbo nucifera) waited a millennium, nestled in the peat of an ancient Manchurian lakebed. Robert Brown, a paleobotanist and first Keeper of Botany at the British Museum, successfully germinated desiccated water lily seeds in 1850 after they had been stored away in a box for 150 years.”[4] The example of the seed unrolls how any state of presence is dependent on concepts of sentience and perception. Thinking from the perspective of the seed, the long period in the box is as much a form of presence as is the sprouting after Robert Brown’s germination attempt. The specific physicality and movements make presence legible while taking shape in space. And the spatial dimension of presence intertwines the local and the cosmological, at the same time expanding at the site as well as presenting a signature in the strata of presences. Again, the example of the seed and its distinct states of awareness and temporality is not only helpful to illustrate how it is not a self-reflexive system but enmeshed in the entirety of seeds and their sprouting timelines. It also serves to question the boundaries of “being seed,” other or unusual routes and routines of sprouting, not sprouting, withering, and rotting.

Ernst M. Kranich’s cosmological view on botany explores the importance of rhythm research, the movement of planets and asterisms, and their effects on organisms. His observations of plant life take on a planetary perspective, a kind of nonperceptual sensation where everything is present, largely influenced by the thinking of Rudolf Steiner. He indicates “specific relationships between the spiral leaf arrangement and the revolution of the planets,” which should not be considered as a scientifically based statement but rather as pointing to another direction of investigation.[5]Kranich continues to explore the rhythmical coordination of the planetary system in detail and the connectedness of vegetal morphologies and planetary systems. For example, he asks whether “a reflection of the ascending movement of the sun is found in the center shoot of the herbaceous plants” and asks how one then should consider the other organs of a plant in relation to the sun and other planets.[6]He includes several rather schematic line drawings to illustrate his arguments, which indirectly also express the difficult undertaking of his research. It is either a representation of the plant or a drastically reduced scheme of planetary movements, drawn as lines and symbols referring to activities and constellations that are, due to their immense scale differences across time and space, hardly translatable. Rudolf Steiner proposes an intuitive, sensory approach in order to discover and comprehend; Kranich adds Goethe to further specify that “the eyes of the spirit and the eyes of the body must continuously work together lest there be a danger of looking and yet overlooking.”[7]He concludes that if one would allow oneself to exercise an imaginative perceptual state receptive to the rhythms of planets, the “formative processes of the plants” would appear as “the living reflection of the universe.”[8]However, Kranich’s understanding of cosmology neglects the gravity of distant galaxies and remains on a symbolic level, which his drawings underline.

To leave the symbolic behind and render perceptible what is impossible to perceive was one of the intentions of early time-lapse photography. The challenge to build optical and mechanical instruments of scientific observation able to cut through different temporalities and speeds to explore plant life’s rhythms and activities is evident in prominent examples from historic plant studies. These include the works of filmmaker Max Reichmann, such as Das Blumenwunder(“The Miracle of Flowers”) (1926), a silent time-lapse film of flowers’ motion accompanied by dancers—children moving in a plant-like manner suggesting to bridge the gap between plant and human.[9] This work, along with earlier scientific films on plant movement, such as Wilhelm Pfeffers’s Studies of a Plant Movement (1898–1900) or Percy Smith’s Birth of a Flower (1910), demonstrates a peculiar porosity between human and plant. The films are a representation of a performed change in the resolution of time and show a mode of plant presence otherwise hidden from the human eye. In particular, the curling and unfolding of leaves and petals are used to communicate and recognize the range of motion and sensitivity in species that have been regarded as inert and passive. The medium of film certainly has the capacity to refine and access the universe of imperceptible movements and scales, while the technology of recording itself is a mode of inscribing signatures of presence onto light-sensitive material or a memory card. Possibly invoking doubtful human/plant attunement, the experience of seeing the potential of another species’ spectrum of perceptive activity might enrich one’s own range of being-in-the-world in the collective sensorium of presence-ing. Interestingly, with most mediated engagements, the plant remains in the position of being something “to be activated”; forms of absences are rarely considered.

Philosopher Alva Noë argues that human vision in relation with bodily movement functions as perceptual consciousness, in the sense of sensorimotor access, to the world. Noë distinguishes between a sense of presence that acknowledges the spatial distribution of things, a there, with the perceptive ability to actually see it appearing in sharp focus. Thus, things can be present and at the same time occluded, hidden, invisible—out of view. This suggests a direction quite different to Despret’s telling of the passenger pigeons, which proposes thinking perspective not as focus or out of view. Instead this line of inquiry points towards a kind of knowing at a distance: According to Noë, presence is also absence but follows a spatial logic derived from an understanding dominated by the limits of vision and ways of seeing. Specifically, “the fact that we visually experience what is occluded shows that what is visible is not what projects to a point. I propose, instead, that we think of what is visible as what is available from a place. Perceptual presence is availability.”[10]The idea that something is here—or, as Noë terms it, amodally present—but not necessarily in one’s focus or degree of access is also helpful for thinking the temporal and spatial distances of vegetal expressions. The time-lapse experiments of early twentieth-century filmmakers accommodated unknown possibilities of seeing plants and made a particular presence of the vegetal available to us—accessibility that is dependent on different repertoires of skills that open the world’s visual presence, tactile presence, and so forth. The relations emerging through the respective technologies of presencing rely on modes of attention mediating across the different perceptive spheres. These are rehearsed in experiences such as the time-lapse recordings and other experimental constellations.

Another aspect of the spatiorelational conditions of presence are simulated or virtual scenarios. “The environment entails traces of the operation of presence,” writes performance and new media scholar Gabriella Giannachi, who further specifies, “in other words, presence is also an ecological process that marks a moment of awareness of the exchanges between the subject and the living environment of which they are part.”[11] This awareness configures processes of orientating and positioning in space and among all species. The possibility of presence across virtual and physical worlds facilitates a relocation of experience and points of view, taking shape as forms of remote presence, also referred to as “telepresence.” The virtual stretches the sensorimotor boundaries of presence and array of foci as discussed by Noë. Being in more than one place and equipped with a different suite of sensorial abilities and therefore perspectives, out of view attains new significance. To hide one’s presence is increasingly difficult on a planet that is more networked and monitored than ever and where models calculate in order to forecast that which is becoming present; the anticipated presence of weather phenomena being one example. Media and cultural studies scholar Jennifer Gabrys’s writing about the conditions of our computational planet refers to telepresence as “the ability to know things from a distance. Distance presented a new way of understanding mediation: as sensation understood through a more filtered and remote rather than immediate engagement.”[12]Computing environments act within network streams, a planetary force of another kind, a system linking being present across vast distances in different densities, speeds, and qualities of transmission. Attention to the suite of not only computational but also sensorial technologies expands the perspective: “Each technology not only differently mediates our figurations of bodily existence but also constitutes them. That is, each offers our lived bodies radically different ways of being-in-the-world.”[13] The exquisite technologies of plants in making contact with and across the world through their kind of sensorimotor capacities allows them to have correspondences, to spread in space, to write, read, and encode.[14]These signatures tell of presences that are different and, through being collectively witnessed, rendered similar yet never the same. Anthropologist Stefan Helmreich studies the work of astrobiologists in their search for the presence of extraterrestrial life. It promises an exciting exploration of mediating forces tracing expressions of presence beyond the visual: “The signature of life can exist only insofar as life itself is a replicable absence, a metaphysical quality we know when we don’t see it.”[15]Their main occupation is to look for remote signatures and indices, another practice of sensing presence in the many absences and modes of being-out-of-view that require critical consideration. We need to follow Despret’s stance, which reminds us that everything is sensing and being sensed by everything, and further, that “what the world has lost, and what truly matters, is a part of what invents and maintains it as world.”[16]

Notes

[1] Vinciane Despret, “It Is an Entire World That Had Disappeared,” in Extinction Studies: Stories of Time, Death, and Generations, ed. Deborah Bird Rose, Thom van Dooren, and Matthew Chrulew (Columbia University Press, 2017), 219.

[2] Despret, “An Entire World,” 221.

[3] Emanuele Coccia uses the analogy of the seed for describing the form of being in engagement with the world as cosmic; he writes, “to exist, the plant has to merge with the world, and it cannot do so other than in the form of a seed.” The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture(Polity Press, 2017), 14.

[4] “His careful experimental attentiveness to Nelumbo was characteristic of Victorian botany of the time, in which the verdant wealth of the empire was amassed in the gardens and herbaria of Britain as both a scientific resource and a spectacle of colonial might. The upper limits of seed dormancy were also, in the mid-nineteenth century, of increasing interest to Charles Darwin, as seed viability could impact how widely a plant might disperse.” Sophia Roosth, “Life, Not Itself: Inanimacy and the Limits of Biology,”Grey Room 57, (Fall 2014): 63.

[5] Ernst M. Kranich, Planetary Influences Upon Plants: A Cosmological Botany, trans. Ulla Chadwick and John Chadwick (Bio-Dynamic Literature, 1984), 4; see Rudolf Steiner, Die Geistigen Wesenheiten in den Himmelskörpern und Naturreichen (Rudolf Steiner Publishing House, 1974).

[6] Kranich, Planetary Influences Upon Plants, 26.

[7] Kranich, Planetary Influences Upon Plants, 166; see Goethes naturwissenschaftliche Schriften, vol. 1, 107.

[8] Kranich, Planetary Influences Upon Plants, 166.

[9] Zoe Schlanger. “Vibrant Bodies, Electric Beings.” In Green Modernism: The New View of Plants. Museum Ludwig, September 17, 2022–January 22, 2023: 1 (pdf).

[10] Alva Noë, Varieties of Presence (Harvard University Press, 2012), 19.

[11] Gabriella Giannachi, Nick Kaye, and Michael Shanks, Archaeologies of Presence: Art, Performance and the Persistence of Being (Routledge, 2012), 53.

[12] Jennifer Gabrys, Program Earth: Environmental Sensing Technology and the Making of a Computational Planet (University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 65.

[13] Vivian Sobchack, “The Scene of the Screen: Envisioning Photographic, Cinematic, and Electronic ‘Presence,’” in Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film, ed. Shane Denson and Julia Leyda (REFRAME Books, 2016), 90.

[14]For an example of a planetary network in regard to plants, see the work of Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton University Press, 2015).

[15]Stefan Helmreich, Sounding the Limits of Life: Essays in the Anthropology of Biology and Beyond (Princeton University Press, 2016), 79.

[16]Despret, “An Entire World,” 219.