Perception

Living things perceive, take account of, and intervene in their surroundings. Certainly since Charles Darwin’s late fascination for and experiments with the Venus flytrap and its reactions to touch and irritation, the vegetal has been situated within an arena of perceptive organisms after centuries of being regarded with insensitivity or reduced to mechanical response.[1] Plants show complex biological interactions, exquisite modes of signaling, and sensitivity to light: expressions that complicate a century-long dispute on the vegetal’s ability to coordinate and integrate mind and movement. Philosopher of science Paco Calvo concludes in a response to psychologist Arthur S. Reber’s Caterpillars, Consciousness and the Origins of Mind that “the behavioral repertoire of plants that supports the capacity for subjective experience in plants [ . . . ] licenses our quest for the origins of mind in plants.”[2]There seems to be little hesitation about manifestations and therefore the existence of plant perception—even though the term “perception” itself rarely appears in scientific literature in regard to plants. Instead, it is mostly plant sentience that is brought up for discussion, albeit in relation to a more primitive form of sentience that does not necessarily imply the interpretation of perceived stimuli. “Perception” weirdly sits in the shade of controversially debated terms such as “intelligence,” “cognition,” or “intuition,” even though it has the potential to act as a transitory contrivance for the positioning of plant subjectivity. Yet, taking a closer look at what perception entails—an exquisite knowledge that dwells in the specificity of sensorial encounters with the world—sets in motion the “how” of perceiving and perhaps complicates our understanding of it. The perceptual capacities of plants, animals, and humans differ in their resolution, transmission speed, and spatial disposition as well as other specific attributes attuned to their particular habitat. Speculative, collective forms of responsiveness process perception across species and create proximities. Proximities that are rooted in the creative collaboration of senses, the synesthetic characteristics that dwell in perception: that is body, that is movement. And it is the transformative quality in the relationships between human and plant that propel questions of synesthetic perception. What follows is a brief excursion into questions of collective perception, where resolution and dissolution of perceptive fringes attempt to open up human and plant modes of attention.

They gently rest their weight on a tiny plateau that they just discovered fits the curvature of their mandibular joint. Over time, what initially began as a resting gesture catches momentum again, as the ear slides off the plateau and pulls the rest of the body around the other. The shift of weight freed their bottoms, and they entwine even more. A fine negotiation between giving support and taking off to reach somewhere else.

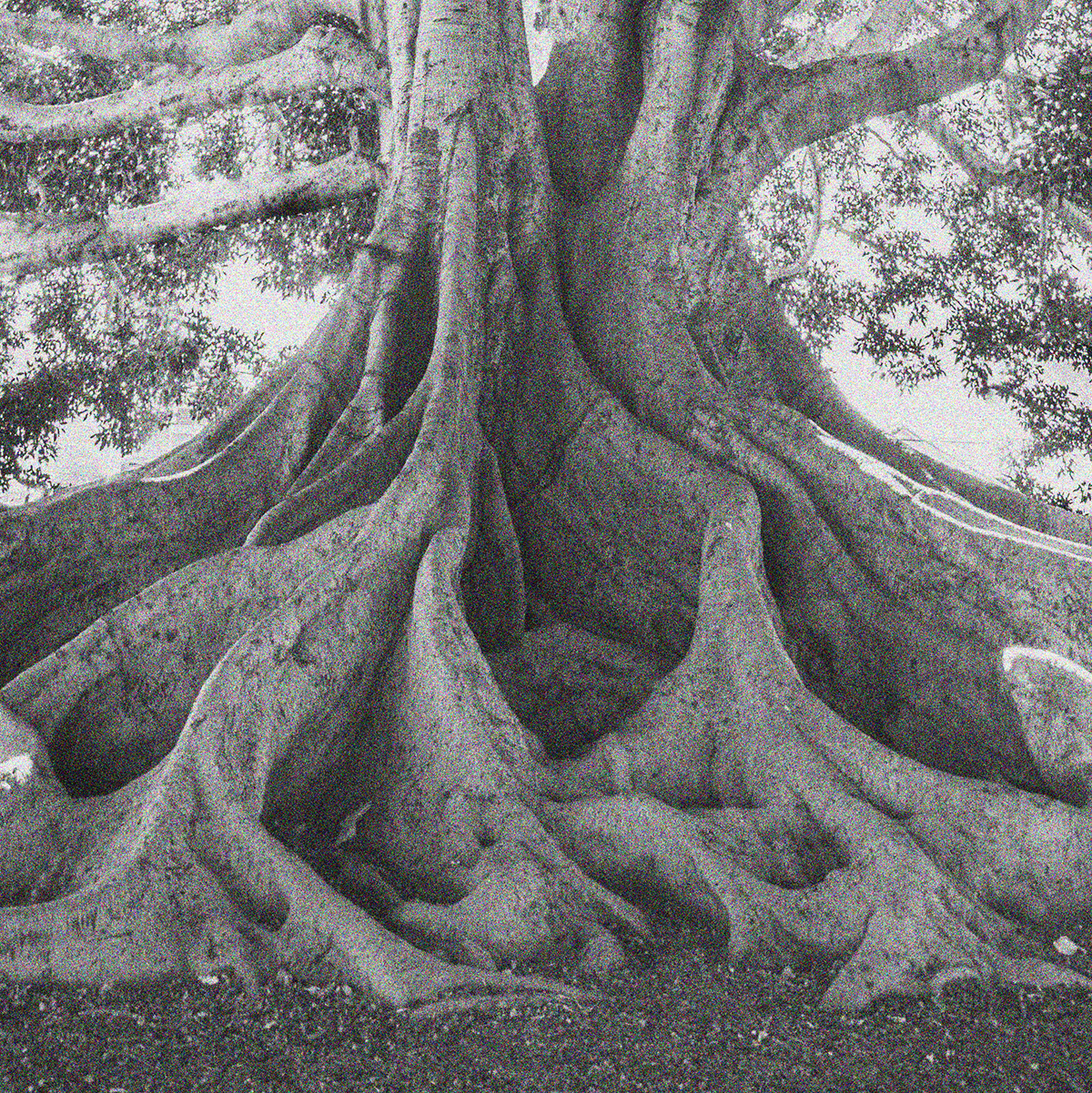

These are words from a choreography of two dancers, Esther and Christina, together with a collective of recorded pea plants, exercising each other’s support structures. Both are politely leaning onto the other’s body in order to facilitate otherwise inaccessible sites of exploration. Esther and Christina follow the study of time-lapse recordings of pea seedlings captured in different time intervals, performing circular motions in their search for anchor points. The seedlings’ proprioceptive sensing—their understanding of movement and their bodily boundaries in relation to the spatial composition—as well as the underlying momentum together posit a complex integration of environmental and sensorial information. Charles Darwin termed the swinging, twisting motion specific to plants “circumnutation,” and he used his own body to experience and comprehend the anatomy of the plant and its structural system.[3] The above choreography, however, is less about mimicking the plants’ behavior, morphology, or movement vocabulary, like the time-lapse silent movies of the early twentieth century. Das Blumenwunder (1926), which remains famous along with other cinematographic experiments of the time that displayed the locomotion of plants, as well as animals and humans, slowed down the “manipulating scale and reconcil[ed] the dissonant temporalities of human and vegetal beings” into temporal increments so they could be perceived by the human eye for the first time.[4] Jean Epstein, theorist and filmmaker who fundamentally influenced early cinema, explained that the unsettling dimension of film utterly changed the seeing, feeling, and conceiving of reality:

The breadth of playing with space-time perspective, games that involve accelerated movement, slow motion and close-ups, reveal movement and life in what was considered immutable and inert. Through accelerated projection, the scale of the kingdoms is shifted—more or less, depending on its relationship with acceleration—towards a greater qualification of existence. Thus, crystals begin to vegetate in the manner of living cells; plants come alive, choose their sources of light and sustenance, express their vitality with movements.

[5]

In the movement research performed by Esther and Christina, together with an artistic and scientific team for the project “Unstable Bodies” (2021–2024), the memory of witnessed gestures, their physicality and rhythm, is introduced as sensorial artifacts transposed into and across bodies and spaces. In attempts to find the nuances of articulation in one’s own body in correspondence with others and letting go of preconceived assumptions, modes of perception and realities collide, intermingle. To find those nuances, subjects leave familiar traits behind, trusting the decomposition of bodies, their disparate timings, their unusual weight. It is an intimate, at times very slow, internal view. Letting the eyes rest in their sockets, they are freed to perceive at their perimeters rather than having to focus at familiar distances. It is thus that unseen fringes become activated. In this other, unknown state of attention, twisted motions are reintroduced: drastic slowing down, altering weight, shifting body-plant parts.[6] Explorations of weight-shifting, finding support structures in order to trick gravity and catch momentum to propel beyond physical limitations, were fundamental to researching movement vocabularies across body-plant; these observations were based on time-lapse recordings of pea plants, among others:

Gravity is the most permanent, constant force among all environmental forces acting on plants. This explains why all plants have evolved sensory mechanisms that detect the direction of the gravity vector with uncanny accuracy, using it as a compass. All plants and their organs move in directions that are tightly coupled to the direction of the gravity vector. These are designated gravitropic movements, and they are guided by gravity in one, two, and three dimensions.

[7]

Plant scientist Elizabeth Van Volkenburgh highlights the work of botanist Dov Koller, author of The Restless Plant (2011). Koller paired growth physiology and movement in order to explore the seeking, sensing, and responding aspects of plants’ engagement with their environment. Another intriguing example of responsive activity complicating internal and external stimuli is the study of dinoflagellates Pfiesteria piscicida, so-called fish killers, as well as the controversy about their toxicity, which was investigated by science and technology studies scholar Astrid Schrader. The latter argues that phenotypic plasticity, in reference to biologist Scott Gilbert, is the skill to adapt to external conditions by changing oneself and is insufficient to explain the observed phenomenon. The particularity of these organisms, which can never be captured in their entirety, is the dissolution of the “very distinction between internal or innate characteristics and externally or environmentally induced behaviors.” She continues, “Boundaries between organism and environment do not simply become blurred, but rather the entire process of boundary construction has to be reconfigured in order to account for the entanglements within Pfiesteria’s.”[8] Thinking with Astrid Schrader’s observations, awareness of the body in space is fostered by the synesthetic modalities informing bodily tissues. For example, cell walls are in correspondences with their habitat and thus co-constitute their place in the world. This ultimately situates perception as inseparable from organism and environment.

He looked up at last. He saw me as I have never been seen before, not even by a child, not even in the days when people looked at things. He saw me whole, and saw nothing else—then, or ever. He saw me under the aspect of eternity. He confused me with eternity. And because he died in that moment of false vision, because it can never change, I am caught in it, eternally.[9]

In the voice of an oak tree, science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin narrates the perspective of a plant dwelling at the edge of a road. She takes us along the tree’s memories, of the days when the travelers’ speed was still modest, had a different, more enchanting rhythm, and allowed for moments of catching each other’s gazes, of making contact (a sort of greeting, maybe). This kind of a mutual encounter seems possible due to the plant’s ability to assimilate its morphology to the surroundings’ stimuli and, importantly, their timings. In its assimilation efforts, the tree weirdly “scales” itself to meet with the other, “to grow enormously, to loom in a split second, to shrink to nothing, all in a hurry, without time to enjoy the action, and without rest.”[10] The tree’s perceptual engagement with its surroundings, its physical responses triggered by the passing traffic, sound like a stressful burden. Yet, throughout the short story, The Direction of the Road, the scale of perspective resides within a human frame of reference despite the fact that the voice the reader listens to is an oak tree. At least, the telling from the plant’s point of view may hint towards an idea of dimensions of scale in regards to perception. The very position of sensing is not steady; nor is the graininess of the perceived nor the fuzziness of transitioning between scales. The perception of space, time, and intensity is considered intermodal and fuses individual sensory capacities together. If perceptive conditions deviate or are absent, then other sensory or cognitive mechanisms complement or even amplify the sensation. What scientifically is known as “amodal”[11] could hint to a (dormant) ability to activate and entrain modes of sensing, maybe equipped or sufficiently creative to engage in other resolutions of perception. Le Guin attempts to throw perception around, letting the oak speak from the eyes of a motorcar driver in the moment just before their collision. “False vision,” she calls the instant of actually seeing fully, of him seeing with his entire body, seeing the entirety of the tree body and their meeting of images: imaginaries caught forever in the tensed construct of these disparate frames of perception colliding. Such intertwining of the senses, as philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty persuasively elaborates, refuses a linear notion of experience. Instead, it shows how perception is synesthetically enmeshed, how it not only reads and references across its sense organs but also how “an anonymous visibility inhabits” more than one body, “radiating everywhere and forever.”[12] Or, put differently, each sensation is also universal; it carries in it all that it is not in that moment. This means a space of sensorial negotiations, of synesthetic nature, which incorporates and is informed across present times, future and past, as well as bodily knowledges and patterns: “What is open to us, therefore, with the reversibility of the visible and the tangible, is—if not yet the incorporeal—at least an intercorporeal being, a presumptive domain of the visible and the tangible, which extends further than the things I touch and see at present.”[13] This intercorporeal being suggests a space of communication and depth between bodies, “open to visions other than our own.”[14] Maurice Merleau-Ponty and his phenomenological analysis exemplifies the previously elaborated understanding of perception, in which the surroundings are inseparable from the sensorial apparatus. Experience is always intermingled, a construction of environmental information and a sensory system offering itself in order to emerge together.[15]

Among the many challenges in the engagement with other-than-human entities—in this case, plants—is finding and articulating a scale and resolution in regards to time, space, and body that involves plant body, human body, and instrument body. In this complex graininess of trying to “see” each other, in setting relationships between time and perception, the body, plant body, human body, and its messy in-betweens may present exquisite technologies, some of which might be surprisingly similar. Could we think of a physicality of seeing that is a distributed mode of seeing that is touching, that is tasting? Could that be described as a form of interfacing, as an activity of sur-facesensing, of a “feeling” that allows for an experience that makes the world accessible in different ways? As media theorist Marie-Luise Angerer describes it, that may involve thinking about the inter-val that is present in every sensory experience, the time gap or delay in time that dwells in the thresholds between body and environment and psyche and organism.[16] Angerer understands these thresholds not as dividing principles but rather as a space of operating, forms of translation where affects dwell—negotiating ideas of interiority and exteriority. With every plunge of an eyelid and each rise, in the blinking darkness, the intertwining of the entire body and its sensory dimensions with the world is enlivened.[17]

Notes

[1] See Renaissance plant physiologists Thomas Browne (1605–1685) and Robert Sharrock (1630–1684) for the first experimental investigations into plant sensitivity, entrenched with mystical beliefs of the time: Thomas Browne, The Garden of Cyrus (Golden Cockerel Press, 1658); Robert Sharrock, The History of the Propagation and Improvement of Vegetables (W. Hall, 1672).

[2] Paco Calvo, “Caterpillar/Basil-Plant Tandems,” Animal Sentience 11, no. 16 (2018): 4.

[3] Darwin’s embodied experiments, using his own body to study the plant’s proportional system, among other things, are apparent in his explanations: “The position of the antennae in this Catasetum may be compared with that of a man with his left arm raised and bent so that his hand stands in front of his chest, and with his right arm crossing his body lower down so that the fingers project just beyond his left side. In Catasetum callosum both arms are held lower down, and are extended symmetrically. In C. saccatum the left arm is bowed and held in front, as in C. tridentatum, but rather lower down; whilst the right arm hangs downwards paralysed, with the hand turned a little outwards. In every case notice will be given in an admirable manner, when an insect visits the labellum, and the time has arrived for the ejection of the pollinium, so that it may be transported to the female plant.” Charles Darwin, On the Various Contrivances by Which British and Foreign Orchids Are Fertilized by Insects, and on the Good Effects of Intercrossing (J. Murray, 1862), 235.

[4] Teresa Castro, “The Mediated Plant” e-flux, no. 102 (September 2019): 4.

[5] Jean Epstein, L’Intelligence d’une machine (Éditions Jacques Melot, 1946), 287.

[6] “A surprising animism is being reborn. We know now, because we have seen them, that we are surrounded by inhuman existences [ . . . ] The cinematographer extends the range of our senses, making perceptible to our sight and to our hearing individuals that we considered invisible and inaudible.” Jean Epstein, Photogénie de l’impondérable (Éditions Corymbe, 1935), 251.

[7] Dov Koller, The Restless Plant(Harvard University Press, 2011), 46.

[8] Astrid Schrader, “Responding to Pfiesteria piscicida (the Fish Killer): Phantomatic Ontologies, Indeterminacy, and Responsibility in Toxic Microbiology,” Social Studies of Science 40, no. 2 (April 2010): 283.

[9] Ursula K. Le Guin, The Direction of the Road (Fooslcap Press, 2007).

[10] Le Guin, The Direction of the Road.

[11] “Amodal Perception,” Encyclopedia Britannica,https://www.britannica.com/science/amodal-perception.

[12]Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible (Northwestern University Press, 1968), 142.

[13]Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, 142.

[14]Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, 142–143.

[15]Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Structure of Behavior (Beacon Press, 1963), 13.

[16]Marie-Luise Angerer, Nonconscious: On the Affective Synching of Mind and Machine (meson press, 2022).

[17] The idea that plants may have “eyes” is not new. In 1907, Francis Darwin, Charles’s son, hypothesized that leaves have organs that are a combination of lens-like cells and light-sensitive cells. Experiments in the early twentieth century seemed to confirm that such structures, now called “ocelli,” exist. In 2016 František Baluška, a plant cell biologist at the University of Bonn, and Stefano Mancuso, a plant physiologist at the University of Florence, provided some evidence for visually aware vegetation. They refer to the cyanobacteria Synechocystis, single-celled organisms capable of photosynthesis, that act like ocelli. From their article in Scientific American from January 2017, “Do Plants See the World Around Them?”: “‘These cyanobacteria use the entire cell body as a lens to focus an image of the light source at the cell membrane, as in the retina of an animal eye,’ says University of London microbiologist Conrad Mullineaux, who helped to make the discovery.”